Fencerows

Nothin's more frustratin’ than turning around all the time just because there's a stupid little line of rocks and brush and trees. When you're drivin' up and down a field, plantin' or plowin', balin' or cultivatin', the longer and bigger the field the better (unless you're some hired hand kid who doesn't care about gettin' anything done and just wants the sun to go down, so he can go home). Well, back some hundred years ago or so when all the farmers around here had cows, they all fenced off their fields, so after the corn they could put the cows out to eat up what they missed. There were more farmers then, too–a lot more. That was back when a family of eight could make a pretty good livin’ off four, five hundred acres, but nowadays everyone has to farm two, three thousand to pay for health insurance that’ll pay for birth control.

So, anyway, because the farms were smaller the fields were smaller. And since the fields all had fences around them, it wasn’t long before the fields all had mulberry hedges around them. (Damn mulberries, the things grow like thistles, but they’re made outta wood, and the berries, if you like ‘em, are only ripe a day before the birds get to ‘em, and then everythin’ gets plastered with purple shit.) And once there’s mulberries the tired old farmers give up and let the oaks and poplars and hickories and maples have at it, and before you know it half the field’s shaded out, and you’re turnin’ around all the damn time.

So, anyway, every fall we tried to take out a fencerow or two, depending on the size. One fall when I was fifteen or sixteen—it was probably the fall I turned sixteen—we took out a big one back on Tyler’s. (We always call farms by the previous owner; it’s very unlike colonialism that way.) Tim Tyler was still around then. He’s the one that hunted deer with a pistol with a scope on it. I remember when I was little watchin’ him hang one of his huntin’ dogs over his shoulder by the choke chain because it tried to bite me. The dog hung there wrigglin’ and stiffenin’ against its master’s back as old Tim (he was in Vietnam) carried on a calm conversation with my dad. The dog was okay, I guess.

So, to take out a fence row: first, you cut down all the trees with a chainsaw, cut ‘em up for firewood; then you pile up the brush and hire out a bulldozer for the stumps; burn the piles; chisel plow where the fencerow used to be; then have your fifteen or sixteen-year-old grandsons pick up rocks and roots and sticks for a couple of years all bent over. Then when you picked up every little piece of wood and stone, you chisel plow it again and there’s twice as many roots stickin’ up as before. And you do this as many times as you can stand it, and then a couple of times more.

So this particular fencerow, the one behind Tyler’s, was down the hills, down north there. Those hills were made by glaciers, and they deposited all that nice loam that gets you 225 bushels a corn an acre. Well, in the bottom of one of these hills was a white oak. I swear I’m not exaggerating: it was sixteen feet in diameter. (I remember because I embarrassed myself by exposing my excessive education by explaining pi to some of the other workers.) So, a sixteen-foot trunk, and forty-foot-long limbs, parallel to the ground, that were bigger around at the trunk than most trees are around here. That tree was majestic. It was huge, and we saved it for last. We talked about leavin’ it, but it shaded out almost an acre, and if you didn’t cut down all the trees it was kinda beside the point cuz you’d still hafta farm around somethin’ and pick up the limbs that storms took off, and brush would grow around it, and before you knew it our grandkids would be farmin’ around a white oak island. So Grandpa said, “Cut it down.”

I was too sad to admit it, and I did kinda want to see it fall. So one of the warmer days in late November or so, Tim Tyler got out his four-cycle chain saw with a seven foot bar. Tyler had a bunch of old weird stuff. He seemed to collect old Ford Broncos, and had one really rusty one sitting on the side of his driveway lookin’ like it’d always roll down the hill. And one day, a couple years later, after we loaded hay out of his barn, my cousin, Scott, was tryin’ to get a stone out of his shoe, and he hung his bale hook on the rusty brush guard on the front of that Bronco, and started takin’ off his shoe. Well, I guess the weight of that hook was enough to start the Bronco rollin’ down the hill. Scott ran out of his shoe to get away and the Bronco bounced down the hill till it hit the old concrete silo. We laughed our asses off.

So we helped Tyler carry that monster of a saw to the trunk of that white oak, and we helped him tie a rope to a limb to help pull it over. Then the rest of us kept the fires goin’ and stayed the hell away from that death trap. We all decided that you had to go through Vietnam before you’d do somethin’ that crazy, and before you could possess such a lack of sympathy for something that big and old, and alive, that you grew up with. Even Grandpa stayed home that day; I don’t think he could bear seeing his orders carried out. It was good to have a chain of command and someone crazy on the business end. So Tyler cut all the way around that tree, and it just stood there. There wasn’t any wind, so it was still standin’ when we went home that night. The next morning it was still there, and the same for two more days, no joke. We were startin’ to get excited thinkin’ that that tree wouldn’t give up that easy. But Tyler cussed and swore at it and wanted to borrow our backhoe to push the fucker over, but that was our only backhoe, and no one thought it’d survive that tree (or Tyler, for that matter). But even by the third day Tyler wasn’t at the end of his rope that was too short. That big ol’ white oak just stood there, lookin’ sad and sturdy down at us. We were startin’ to think that that tree’d keep standin’ there dead on its stump as long as it already had.

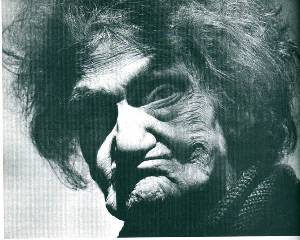

I can remember wakin’ up that night to the whistle of the wind around the barn roof. We all got to Tyler’s earlier that morning than normal, but Grandpa beat us all. He had driven his Cadillac over the corn stubble, but stopped it below the last hill before the big tree. I ran over that hill. Normally you could see the top of the tree’s branches over that hill, but not this morning. When I got to the top of the hill I stopped runnin’. I could see Grandpa. He was leanin’ against the stump, smokin’ his morning cigar, lookin’ down the trunk of the tree to where the limbs pointed toward the sky. He must have heard me draggin’ my feet, and when he looked, I stuck my hands in my pockets and tried to seem disinterested. As I strolled up to where Grandpa was, I was hardly breathin’. I stood next to him for a minute or two and tried to look like I was sizing up the limbs to figure which one to cut off first. I didn’t look at him until he said, “Well.” I saw his face for the first time, and he had the same look that he’d get years later when he was thinkin’ ‘bout Grandma, the same look I figure that General Lee had when Pickett said, “Sir, I have no division.” Grandpa’s eyes were wet, and I was uncomfortable. “Well,” he said slowly, “I think I shoulda let it stand.”

2 Comments:

Excellent.

gosh. good job, luke. (please keep writing.)

.trin

Post a Comment

<< Home